“Everything Believable Between”

I wake up in the same bed I slept in as a boy, in a house Sylvia Plath once likened to a walnut. If I went back in time to the days I shared the room with my brother, the room would look almost exactly the way it does now.

There is not a single door in my parents’ house that hasn’t been warped by the long, cold, wet New England winters. The yard is overgrown, the lawn my father struggled with for so many years has been given over to moss, and my sisters worry about the water in the basement. But if I need a safety pin or a cookie or a hammer, I know exactly where to find it.

I can hear my mother fixing breakfast downstairs and I think back to the days when this small house served as a meeting place for many of the up-and-coming poets of the day, the parties fueled, I realize now, by lots of alcohol. The voices always grew louder as the night progressed, with the smell of tobacco smoke drifting up into our bedrooms from below. I remember running into Robert Creeley unexpectedly in the hallway one time and being taken aback by the glass eye that gave him the appearance, if I were to paraphrase Dickens, of forever looking down the barrel of a rifle.

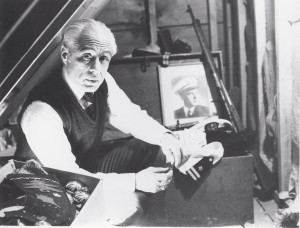

The other poets are long dead now but their fame survives. My father is still alive, but he has never achieved that kind of fame. The man who once shared a stage with Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath has had remarkably few poems published himself. As he himself once wrote, so many ways to fail. Apart from a few slim collections, most of his poetry can be found in sheets of white paper buried throughout his study and on the hard drives of broken down computers we will probably need professional help to retrieve.

A couple of days ago, my mother found one of my father’s rejection slips, this one from the Atlantic Monthly. The year was 1938. “Not quite right for us,” the note said, “but please try us again.” We joke that 70 years is probably not too late to give it another shot.

At the hospital, my father tells the nurse he still has two more books he needs to do. The nurse smiles patiently, and leans in closer because she is not sure she has heard him correctly. Two more books you need to read, she asks him gently? No, my father says. Two more books I still need to write. My father has never been terribly organized. It took him months to write the final paragraph of his last book. There are many books in his head he will never write.

The nurses are kind to my father, and patient with his family, but I still resent the patronizing way they treat him. He may seem like a child now, I want to tell them, but this is a man who has been a father and a poet and a professor. He is also a member of what Tom Brokaw has described as the “greatest generation.” After graduating first in his class at Princeton and then completing graduate school at Harvard and Princeton, he received a commission with the navy and served four years aboard a destroyer during World War II.

My father claims that he stood on the bridge of the U.S.S. Southerland and watched the signing of Japan’s surrender on the U.S.S. Missouri through binoculars. He also says that he was on the first American warship into Tokyo Bay after the surrender.

While I don’t know if either of these claims are true, I do know that some of his best poetry was written during the four years he spent at sea. I think of the poem he wrote describing the directive American troops were given prior to entering Tokyo Bay – “no friendly discourse between the forces and the people” — and then his surprise to see the “hands go out on every pier to meet the forces in the bay.”

My father’s condition worsens overnight, and when my mother and I arrive the next morning at the hospital, the doctor tells us he wants to intubate him. The ventilator will allow my father to rest, the doctor says, and his body to recover from the unexplained fluid that keeps building in his lungs, turning the xrays from black into a milky white. It’s an aggressive measure, and it will be extremely uncomfortable for him.

I’d like to get your father’s permission, the doctor says, but I am having trouble understanding him. He gives us a couple of minutes to talk it over with my father. The man of such careful words has been reduced to only a few.

My siblings have been called and are heading back to the hospital. We will still be able to communicate with him. But this may be the last time he is ever able to communicate with us. We want to wait until they are able to get there.

I explain the doctor’s recommendation to my father. I tell him the advantages. And I tell him about the discomfort.

Ten years ago, after my father suffered a stroke, the doctors told him that he would never again use the left side of his body. My eldest sister was there with him when, still at the hospital, he moved the pointer finger of his left hand for the first time, and the two of them joked how this gave new definition to the cliché about lifting a finger. That summer he played tennis with us at the Cape. Everything is possible with this man.

My father is saying something to me through the oxygen mask and I lean in to try to understand. My father has always chosen his words very carefully. He doesn’t say “yes” or “okay, let’s do it.” What he does say is “great.”

* * * * *

The three poems I reprint in full today are all from the war in Europe.

Oxi, the Greek word for no, is still written out on a mountainside in stone, intended as a signal for the airplanes of the invading Italian and then Germans.

Thermopylae

The gesture

lingers

in the mind

like vapor

from this stream,

a breath

among the peaks

that passes

and is always

passing

forms of failure

faintly

seen and bitter

to taste

the centuries

of pure

refusals and

a word

to mark the hills

omicron chi iota

where they passed.

Destroyers played a major role during the early part of the war in escorting troop ships across the Atlantic. German submarines lingered nearby, preying on the slower or weaker ships that fell behind.

Incoming

The convoy eastbound is not

slow enough

for Pinckney, laboring

to close. The gap

increases and the funnel smoke’s

a sign.

At dusk the static breaks about

her signal.

“Speed four knots the U-boat

trailing on

the surface, do you read me,

Desron? Over.”

In 1944, my father stood on the bridge of the U.S.S. Niblack as the destroyer shelled a beach in southern Italy in advance of a U.S. landing. Twenty years later he returned, this time from land, to a beach he had only seen once before.

The melons: Agropoli

The old man on that beach

comes to mind as I saw him,

stiffly leaning

to his hard melons,

more white than green,

rolling where he pitched them

in a dry boat.

There was no one else on the beach.

I remember his posture,

turned away

so I could not speak.

But what pinched my throat was

drought, the sand,

unshaded afternoons.

Old man, your silence

is like thirst:

no matter what is rotting in

the bay, or in the fields,

if it is fruit let us

speak of it; time

to pay, and to repay.

All Poems Copyrighted By Stanley Koehler