Writing about Covid-19 and the D.C. jail

My father was a poet. For those of us who know his poetry, it has always been fun to go through early drafts to see how each poem evolved. Contrary to the advice you would get from most creative writing teachers, he always went from the specific to the more general. In one of the drafts I have framed in my study, for example, “bough” was scratched out in favor of “tree.” My father never used adverbs or adjectives. And any hint of sentimentality was missing by the time the poem was published.

I take this same Raymond Carver approach when it comes to legal writing. You focus on the facts. You leave the hyperbole to others.

How then do you write about the coronavirus and the D.C. jail? Your original motion asking for release was denied after an emergency hearing that was conducted over the phone. But your client has reached you again. His sister patches him through. He has a headache and fever but he has not seen a doctor. Mostly he is scared. You are his only hope.

You start with the facts. Fortunately, you have some help with that.

Responding to a class action suit filed by the Public Defender Services and American Civil Liberties Union, a federal judge launched an investigation into conditions at the jail that was based on three days of unannounced visits. The investigators found, among other things, that both staff and inmates lacked understanding of basic protective measures, including the proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Staff members often failed to use protective masks and gloves, and the masks that were used were often “ill-fitting and in very poor condition.” The jail made no attempt to enforce social distancing rules, with “well more than five inmates typically out of their cells at a time.” The lack of showers or clean clothes and linens and the inability to maintain contact with family members for quarantined inmates all serve as a substantial disincentive to report symptoms.

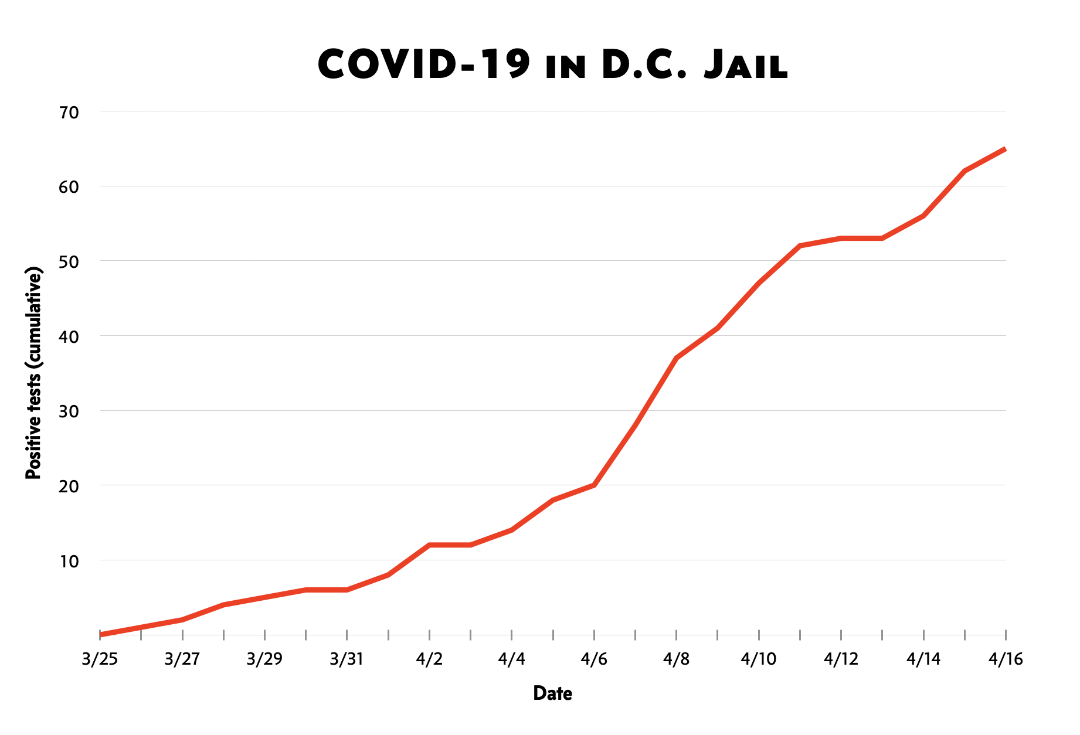

As a result of these conditions, 60 percent of the inmates are currently under quarantine, with 90 confirmed cases and at least one death. Contrary to the prosecutor’s allegations at the hearing that the infection rate for inmates would be equivalent to rates on the outside (and besides, most inmates would survive), the confirmed infection rate for inmates was 15 times that for the city’s population as a whole. The infection rate for jail employees was six times that of the general population.

Next you turn to the relief you are requesting. You know it is an ask. How exactly do you convince the judge to bend the rules?

A number of adjectives come to mind. Fortunately you now have the federal judge’s own words describing the situation as “extraordinary” and “unprecedented.” Government authorities, she finds, are aware of the risks that COVID-19 poses to inmates’ health and “have disregarded those risks by failing to take comprehensive, timely, and proper steps to stem the spread of the virus.” Inmates, as well as society at large, are facing “an unprecedented challenge.” The risks of contracting COVID-19 are very real for those both inside and outside” the jail. The number of inmates being affected grows daily.

Death, she says, is permanent.