Achilles Now. Poseidon Too.

He was the best octopus hunter in Tolo.

It was always an honor whenever he sent one of us boys out to the kiosk to buy him cigarettes: Karelia ke spirta, parakalo. It was an even bigger honor if he invited you along to hunt for octopus. He did the diving. You stayed on the surface, holding onto the octopi he had already caught. He always knew where to look. And he knew exactly where to bite the octopus – once on the outside of each eye — to sap its strength.

Of all the boys in the village who admired him and who competed for his attention, Mitsos took a special liking to me. I liked to think that, as an American, I was different from the other boys. Deep down I knew it was mostly because I spoke English.

The English came in handy with the foreign women who came to Tolo every summer looking for romance. Although his English wasn’t bad and I am sure the women had no idea why he brought this American boy along on all his dates, having me there helped keep the conversation going.

This was the unspoken price of my admission into a world I had never seen before. It gave me a glimpse into what was to come.

* * * * *

My father was also one of his admirers. If you had a photograph of Achilles, my father said, it was certain to look a lot like Mitsos.

Although Mitsos’ father was a fisherman until the day he died, Mitsos himself branched out into other sources of income during the tourist season, renting out paddleboats in front of Aris’ restaurant. As my father once said of him, he has nothing in mind as he walks the beach, or wipes down a boat for the next customer. He is Achilles and a hero still. He is just between events.

If Mitsos looked as Achilles would if Achilles were alive today, then Crazy Andreas, Mitsos’ brain-damaged twin brother, had to have been the spitting image of Poseidon. Standing in front of the statue of Poseidon at the Greek National Museum, all of us came to the exact same conclusion: Oh my God. That is Crazy Andreas.

Crazy Andreas was the young man who, forsaking my three beautiful sisters, decided to woo my mother instead. We would be interrupted at dinner by the sounds of Crazy Andreas calling to my mother from the beach below.

If Mitsos was my hero, Crazy Andreas was my friend. He was just like a ten-year-old who had lived 22 years. Because the village forgave Crazy Andreas everything, hanging with him gave you a license of sorts for all kinds of mischief.

* * * * *

When the Turks invaded Cyprus in the summer of 1974, the Greek junta issued a general mobilization of the military, leaving my father, my brother and me among only a few males in the village. One moment we were swimming with our friends in the Argolic Gulf. An hour or so later, all the men were gone. The news was initially reported – at least where we were — as an invasion of the mainland.

Crazy Andreas was sent back from Athens the same day, or maybe it was the day after. He could never get into the military, a rite of passage for all Greek men, even though he shaved his head every six months or so with the announcement that he had finally been accepted. And Mitsos, to his great disappointment, was posted in Nafplion, just a few minutes away. He too re-appeared in Tolo a couple of days later.

On the day of the invasion, my oldest sister lay on her bed screaming, as she still has a habit of doing today. I just can’t stand it, she repeated as if we had not heard her the first time. In anticipation of our arrival that summer, her boyfriend had his appendix taken out so that he could spend the summer in Tolo on medical leave. But all forms of leave were canceled as soon as the Turks invaded.

He had been in the village for 20 minutes before he had to turn around and take a bus back to Athens. He was in the navy, and did not return that summer.

I knew my father approved of the relationship when we stopped at his base at the end of the summer on our way to the airport. The crisis in Cyprus had settled down, and the junta had been deposed, opening the way for Karamanlis and the return of democracy to Greece.

The military guards did not know what to do with this American family who drove up to the gate and insisted on seeing him. So they produced him. He sat in the car with us for 20 awkward minutes.

* * * * *

My mother wanted to go back to Greece this past summer, and there was some talk about a couple of the grandchildren going with her. In the end, it was my sister who accompanied her. Although I have been back many times, most recently with my wife and three kids, it was the first time my sister had been there in almost 30 years.

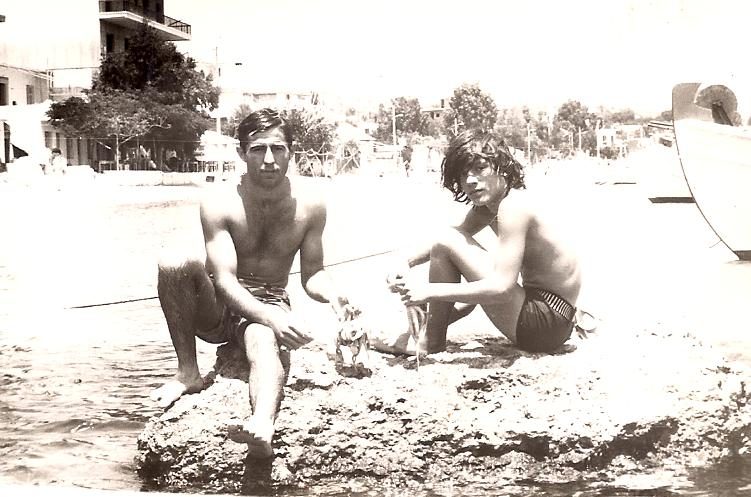

Although Crazy Andreas died many years ago, Mitsos is still fishing during the offseason and tending to his paddleboats during the summer. My sister took a picture of him squatting next to one of his paddle boats. He is just a few feet from the spot where, 40 years ago, he and I had been photographed preparing octopi after one of our hunts.

He is not quite the man he used to be, my sister tells me, and, in fact, of all the photographs she showed me, he is the only person I did not recognize. But the villagers still look out for him, she assures me, just the way they used to look out for his brother.

My sister says she sat with him on the pier in front of the house we lived in that first year and, taking out her new I-Phone, showed him the photograph of the two of us there together. I have always liked that picture. So apparently does he, my sister tells me, this Achilles of today, this hero still.

More like this: