Joyriding With Stanny Bum

Many of the rude words and gestures I know today I learned from driving with my father while growing up.

I didn’t learn these things from my father, because I never once heard him utter a bad word. It wasn’t that using a curse word was in bad taste, though he clearly thought that too. It was that it was intellectually lazy. Why use a profanity when there are so many more expressive words at our disposal? It was like his distaste for exclamation points. Or adverbs. Or adjectives, for that matter.

No, everything I learned was from the other drivers. Though sometimes it was hard to blame them.

My father could be emotionally distant at times – physically present but just not there, lost in whatever happened to be going on in his mind. It was years before I realized he was actually aware of the other drivers making faces at him, and worse.

He just smiled when I asked him about this. I give them mental demerits, he told me.

Later, as a federal manager during my first career, I encouraged employees to use this approach when tangling with someone else in the office. Don’t send an angry email. Take a deep breath and assign mental demerits.

It never caught on.

My father also had a little game he liked to play at a stoplight. He would inch up to the car in front of us to see how close he could get to the bumper without actually touching it.

“You know, Dad,” I said to him when I saw him do this for the first time. “Some people might find that a little bit aggressive.” He appeared thoughtful, almost surprised by this. If there was a modern day expression for the look he gave, it would be: “You think?”

There were complaints about his driving long before he surrendered his license. A neighbor told my mother that, driving down their street on a winter day with snow piled up on either side of the road, she had encountered my father coming the other way. He was driving in the middle of the street, she told my mother. Do you think he should still be driving?

My father was surprised when my mother asked him about this. And annoyed. Of course he was driving down the middle of the street, he said. He was trying to protect his treasure – the Mercedes — from the salt in the snow drifts. My parents treated my father to the Mercedes after all five of their children finished school. The last time I looked, the Mercedes had only 30,000 miles on it. My brother drives that car now.

I first raised my father’s driving with the boss of the family, my oldest sister. It was an easy thing for me to bring up. Living 400 miles away, the burden wouldn’t fall on me to drive him around. And then I raised it with her again. I’ll get to it, she promised. I’ll get to it.

And then it happened: I returned to Amherst to find that he was no longer driving. My sister gave me that “don’t ask” look when I mentioned it. My father only complained about it occasionally, usually when one of my sisters was at the wheel. He wasn’t sexist, really, but he did think my brother and I were better drivers.

My father preferred to walk to the university anyway, the office he kept at UMass two or three miles away from our house on Hills Road, though he did occasionally struggle on the hill. “Stan, you’re bleeding,” my mother said to him one time upon picking him up.

A former student told us of driving down Clark Hill Road to find my father lying by the side of the road. He must have slipped on some ice. My father allowed himself to be helped to his feet, but he would not accept a ride. I’ll be fine, he told the student. It really is a beautiful day for a walk.

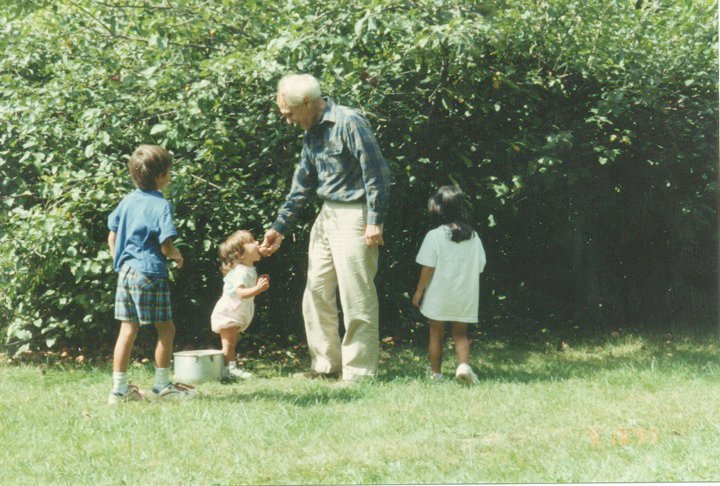

A couple of weeks ago, back in Amherst for Easter, I accompanied his wife, his children and many of his grandchildren to the cemetery where he is buried. It is the same cemetery in which he taught all of his children to drive. It is where he drove with his grandchildren standing up through the sun roof of his Mercedes, the “Schiebedach,” so that they could enjoy the sun and the wind.

On the side of the hill where his ashes are buried, snow drops push up through the wet dirt by his grave. Worms are the dear familiar, he wrote, moisture everywhere. Water through wood communicates. What he asked was to be taken in.