Ralph Who? The Basketball Great You’ve Never Heard Of

In 1981, John Thompson was able to convince two of the top high school basketball players in the nation to come to D.C. to play for Georgetown. Landing either recruit would have been a major accomplishment; getting both seemed too good to be true. There was lots of debate on campus as to which player would be better.

In 1981, John Thompson was able to convince two of the top high school basketball players in the nation to come to D.C. to play for Georgetown. Landing either recruit would have been a major accomplishment; getting both seemed too good to be true. There was lots of debate on campus as to which player would be better.

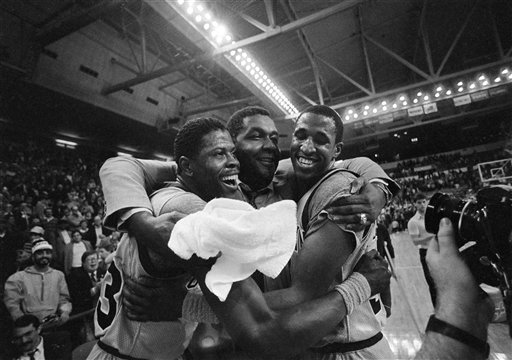

You have undoubtedly heard of the first player of this duo. That was Patrick Ewing. After leading Georgetown to three NCAA championship games, Ewing played on two U.S. teams for the Olympics, including the “Dream Team.” He was eventually inducted into the Hall of Fame as a New York Knickerbocker.

Chances are good, however, that you have never heard of the second member of the duo, Ralph Dalton. That is because Ralph Dalton seriously injured his knee in an intra-squad scrimmage before playing his first game as a Hoya, missing the entire 1981-82 season, and, although John Thompson kept him on the squad for the next four years, Dalton was never again the same player. He did not play in Olympics. He was not inducted into the Hall of Fame. He did not even go pro.

I was thinking of this today while reading comments from another famous Georgetown basketball player, Alonzo Mourning, who played for the Hoyas after Ewing and Dalton. It is not just the stroke of luck that had one promising prospect – Patrick Ewing — going on to fame and fortune and the other, well, going on. (To be fair, Ralph Dalton did enjoy a very successful non-basketball career on Wall Street.) The question is also how we avoid exploiting our college athletes.

According to Liz Clarke of the Washington Post, Mourning is grateful for the four years he spent at Georgetown. The “current crop of under-age phenoms,” he suggests, should take the long-term perspective: “The benefit of them staying in school and developing a stronger intellect and helping them made better decisions will help enhance the accomplishment of that next level, so that they can take care of their families for years and years to come.”

That, of course, is easy for Mourning to say. He himself made millions of dollars as a pro player after he graduated from college. It is harder to take that long-term perspective when you need to provide financially for yourself and your family immediately.

Who knows what Ralph Dalton would do now if he had it all to do over again? Although bad luck is bad luck, and he could just as easily have injured himself during an intra-squad scrimmage as a professional, at least he would have that first contract and signing bonus to tide him over for a while anyway. And he could have been insured.

Colleges and universities have been making money off the backs of these athletes – billions of dollars — for far too long. I am intrigued by the notion of college athletes unionizing. Promising athletes should be insured. Universities should increase the value of a scholarship, as Mourning suggests. And the NBA should get rid of the “one-and-done” rule. The athletes should be able to make their own decisions when to go pro. And the question of player maturity will be worked out through the marketplace.